Racism was a topic the Precious Blood Sisters reflected on during the last year, and the Leadership Conference of Women Religious Virtual 2021 Assembly also discussed it. This complex topic continues to need attention, so this piece continues our conversation about race.

Sister Eleanor McNally, who has Cherokee ancestors in her family tree, was born in Hollywood, California, in 1918 and entered the Sisters of the Precious Blood in 1933. Her reflection on Native American history was recently published in our e-newsletter, This Good Work. We share it here in light of Pope Francis’ recent apology for “the deplorable conduct of members of the Catholic Church” at residential schools for Indigenous peoples in Canada.

“How could we look at the poverty and destitution of the ‘Indian’ peoples living in poor reservations and not recognize the sins of our nation?” Sister Eleanor said. “I guess what we are trying to do now is to learn and make up for the past even though we were not there ourselves. There’s a mystery about history that weighs on our shoulders that will pain us till the truth is revealed.”

The candles burn low as I see the spirits of my Cherokee ancestors in heart-wrenching tears leave the courts of “American Justice.” Ancestral lands of Georgia and South Carolina, their homes, all that was theirs, is being taken away. I see their long journey west, the “Trail of Tears,” where disease, exposure to winter snows, and starvation spelled death to half of the 16 thousand souls who began the long walk. Tribe by tribe, death by death, the journey of their tears is multiplied as white settlers take possession of native lands.

The scene above gives only the tip of the iceberg to the scourge of racism that followed the indigenous from 1492 till well into the 20th century. Native population on land that would become the United States was estimated at 7 million to 10 million with the arrival of the Europeans. As demands for land on the part of the new settlers followed, it soon became clear that the war between the white man’s civilization and the natural world of the Native Peoples was here to stay.

Before long the government echoed the cry of the settlers that Native Peoples and the whites could not live together. The indigenous were different in color, and in cultural and religious aspects. They were frightening, and so they were portrayed as pagan savages who must be killed in the name of civilization and Christianity. Insulting to the Native Nations’ high cultural development, even missionaries preached with the conviction that the indigenous “had minds and hearts hitherto uncultivated.” Walt Whitman, a famous American poet, commented about Black Americans and American Indians grossly with these words: “The [n—–], like the Injun, will be eliminated. It is the law of the races, history.”

ELIMINATION came in two ways. First by massacres. Mothers watched their children slaughtered before they and the elderly fell to the hatchet or bayonet. Names like “The Creek War,” the “Mankato Executions,” the “Sand Creek Massacre,” “Wounded Knee” of South Dakota, plus many others decimated the Native population. In the end could be counted 1,500 wars, raids, and attacks initiated by the government.

ELIMINATION, secondly, came by way of disease and starvation. Here the story of the slaughter of the buffalo, a great source of food and clothing for the Native Peoples, must be recognized. The U.S. Army deliberately slaughtered the bison, reducing the herd of an estimated 20 million to 30 million to 300 buffaloes. By 1900, the population of the Native Peoples was reduced to 237 thousand souls.

RELOCATION of the Indigenous from their ancestral lands, as in the Cherokee story, was never-ending until the Pacific coast was reached. Lands rich in promise, lands laden with gold became the white man’s possession, treaty or no treaty. Ultimately the “Indian” was reduced to life on a “reservation.”

Andrew Jackson, who “graces” our $20 bills, is referred to as a “genocidal sociopath” by historian Roxanne Dubar-Ortiz in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Jackson, a self-named Indian hater, wrote that indigenous peoples “in the midst of another and a superior race … must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.”

ASSIMILATION became the final effort on the part of the U.S. government to resolve the “Indian” problem. “Kill the Indian; save the man” became the cry: Deprive them of their culture and lifestyles, their ancestral religion and language, their customs, their dress, all that made them unique in the family of nations. Make them Americans. Start with the youth. And so the Indian boarding school was created. Once again cruelty was inflicted. Children were snatched from their homes, some sent hundreds of miles away where, in deprivation of all they knew and loved, they were exposed to “Americanization.” Schools were often overcrowded and disease-ridden. Malnourishment was common, and corporal punishment often inflicted. In such conditions it is no wonder that the mortality rate in those years, which lasted up to the mid-20th century, is estimated at 20%.

Although Native Peoples still suffer from the effects of racism, they have survived to contribute their rich spirituality and heritage to our U.S. culture. With rosary in one hand and Kleenex in the other, I have explored the history of the Native Peoples of the U.S. I invite you to do the same. The candles still burn.

Story by Sister Eleanor McNally

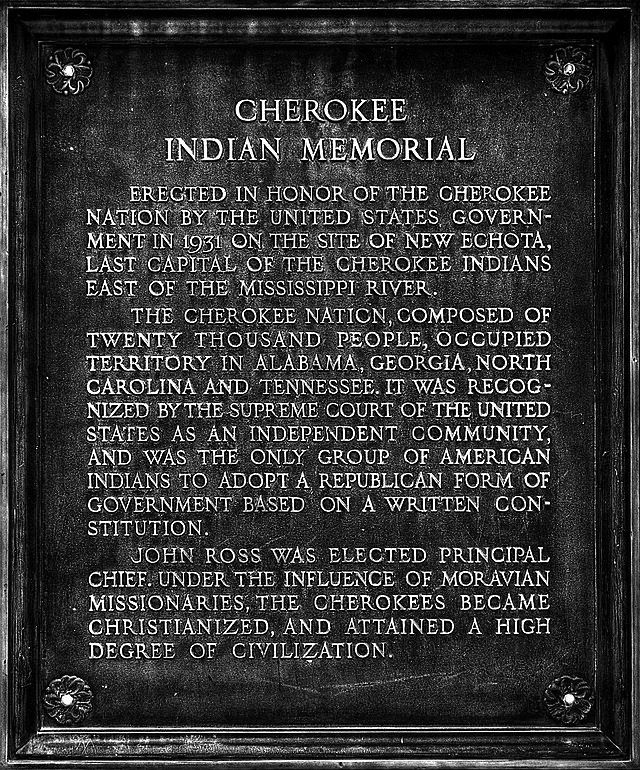

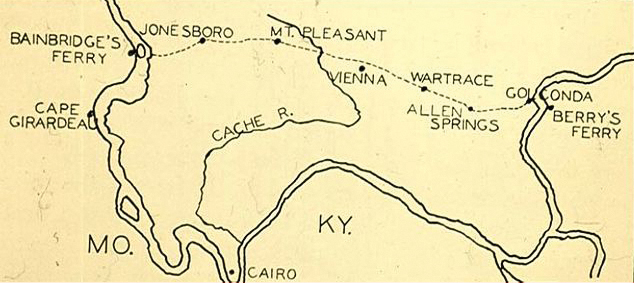

Top, Cherokee Indian Memorial sign at New Echota Historic Site; middle, a Trail of Tears map of Southern Illinois from the USDA – US Forest Service; bottom, Elizabeth “Betsy” Brown, a Cherokee Indian, was on the Trail of Tears; contributed photos.

Top, Cherokee Indian Memorial sign at New Echota Historic Site; middle, a Trail of Tears map of Southern Illinois from the USDA – US Forest Service; bottom, Elizabeth “Betsy” Brown, a Cherokee Indian, was on the Trail of Tears; contributed photos.